Quick

Links:

Week 2 Lecture Slides

Week 2 Lecture Slides (in pdf note form)

Audio lecture m4A

Research Exercise

1: The

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

Practical

Exercise 2: Meaning and Connotative vs Denotative Meaning

Research Exercise 3: Carbon tax and other 'dirty' language

Flash

tutorial: More on eliminating wordiness

Week 2 Style Exercises

Language & communication practice

The theme for this week is Language and how it influences the available choices for professional writers (and speakers). However, a mistake many novice writers (and speakers) make is to assume that language is a neutral medium and that words mean the same to all readers (and listeners). For this reason, we have decided to spend this week exploring some of the theories and issues of language use (a hard task in just one lesson).

Before we go on however, it is important to take a step back and think about how the main tool we are working with as writers, that is language, works. For an introductory overview of some of the issues, read the chapter titled 'Language and Communication Practice' by Archee et al (2012) from their book Communicating as Professionals (3e). This gives a good overview of this topic.

You might also find this link to a Yale University lecture (59 mins) on language and thought useful. This lecture reviews two topics: communication systems in non-human primates and other animals, and the relationship between language and thought. The rest of this lecture is spent on introducing students to major theories and discoveries in the fields of perception, attention and memory. Topics include why we see certain visual illusions, why we don't always see everything we think we see, and the relationship between different types of memory.

Sapir and Whorf – The relationship between language & thought

So how does language impact on how we experience the world? Australian author Dale Spender (see her 1985 book Man made Language), says that:

[l]anguage helps form the limits of our reality. It is our means of ordering, classifying and manipulating the world. It is through language that we become members of a human community, that the world becomes comprehensible and meaningful, that we bring into existence the world in which we live. (Spender,1994, 3)

She is arguing that language is a vehicle through which we understand the complexities of our world. In other words, language is a vehicle which both reflects and is a reflection of our world. However, to what extent are language and thought related? Does language shape our perceptions and to what extent do the language choices we make as writers or speakers reflect our view of the world?

Historically, an important and influential theory on the relationship between thought and language is the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis which theorizes that thoughts and behavior are determined (or are at least partially influenced) by language. If true in its strongest sense, the sinister possibility of a culture controlled by Newspeak (a la 1984) or some other language is not just science fiction. Since its inception in the 1920s and 1930s, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has caused controversy and spawned research in a variety of disciplines including linguistics, psychology, philosophy, anthropology, and education. To this day it has not been completely disputed or defended, but has continued to intrigue researchers around the world.

Research

Exercise 1: The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

Do some background reading on the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and summarise the main arguments being made. Do you agree or disagree with the basic argument that we cannot have thought without language or that our language shapes our thoughts? Write 500 words.

Here are a few links to help you.

- Daniel Chandler in his 1995 book The Act of Writing gives an overview of Sapir-Whorf . The whole book is available online and is quite a good introductory resource for this topic

- http://www.usingenglish.com/speaking-out/linguistic-whorfare.html

- http://www.angelfire.com/journal/worldtour99/sapirwhorf.htm

For arguments against the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, you might try these references:

- Stephen Pinker (1994) The language instinct: How the mind creates language, New York: Harper (a copy is available in the UWS Library). In particular, see chapter 3, 'Mentalese'

- Daniel Casansanto (2008) Who's afraid of the Big Bad Whorf: Crosslinguistic Differences in Temporal Language and Thought (read the abstract and then download the paper if you want to read in more detail

The Meaning of “Meaning”

Where are meanings determined? In the mind of the writer (or speaker) or in the mind of the reader (or listener)? Lewis Carroll had a few ideas.'I don't know what you mean by "glory",' Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. `Of course you don't -- till I tell you. I meant "there's a nice knock-down argument for you!"'

`But "glory" doesn't mean "a nice knock-down argument",' Alice objected.

`When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, `it means just what I choose it to mean -- neither more nor less.'

`The question is,' said Alice, `whether you can make words mean so many different things.'

`The question is,' said Humpty Dumpty, `which is to be master -- that's all.' ................. from Lewis Carroll Alice in Wonderland

Another well known linguist, Deborah Cameron (1995) writes that:

[i]t is a cherished notion that speakers have total control over the meaning of their own discourse and that all linguistic codes are unproblematically shared.

Cameron is arguing here that, words do not mean the same

to everyone and that just because we intend a particular meaning, does

not guarantee that our readers will interpret the words in the same way.

Often the meaning is determined by the context. Here's an interesting piece

from the regular SMH “Words” column, written

Denotative and Connotative meaning

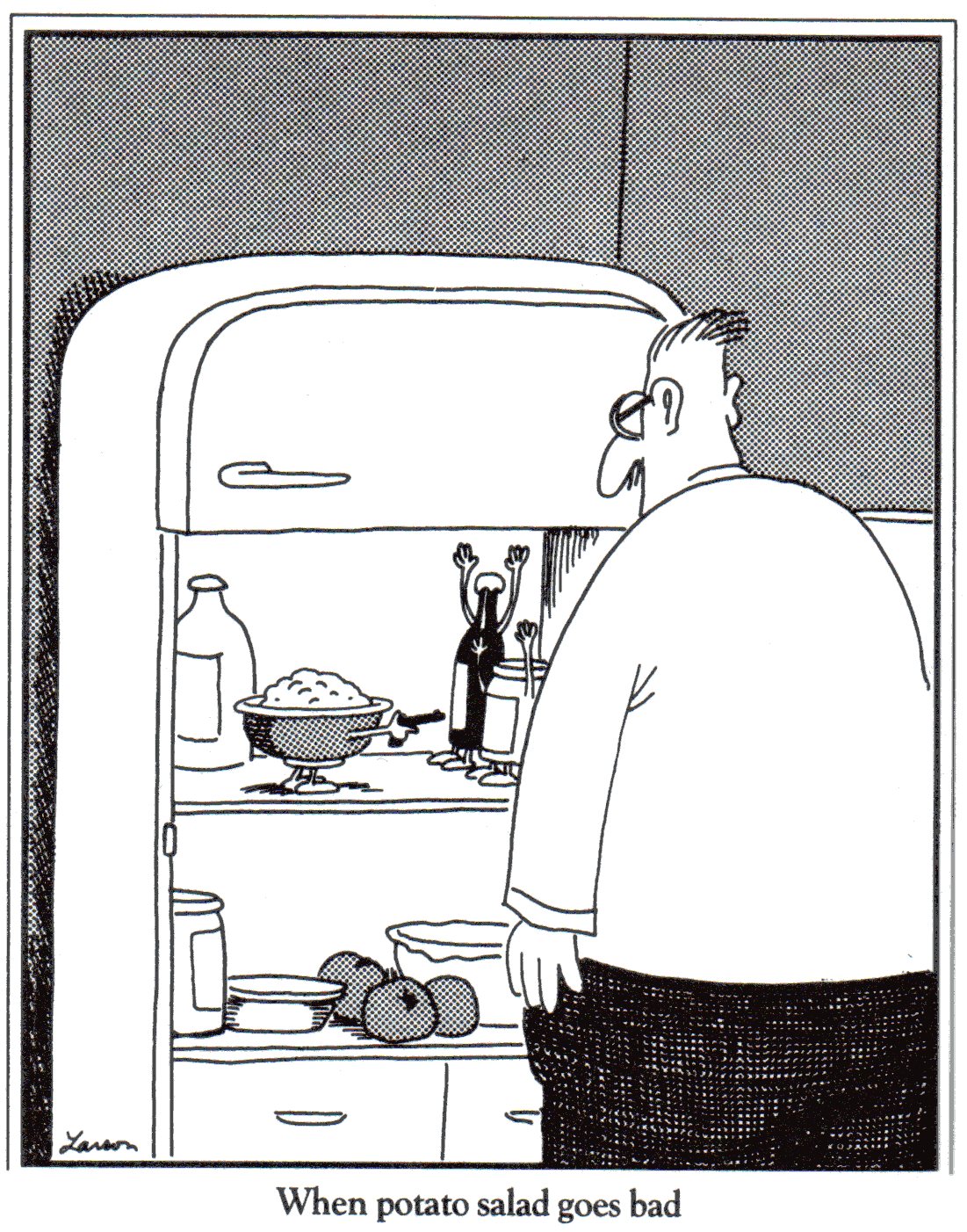

Words often have both connotative and denotative meanings. The denotative meaning is the "literal" or dictionary definition of a word. However, because language is fluid, alive and ever evolving, these words often take on different emotional baggage which impacts on how we understand the meaning in different contexts. The emotions and feelings that a word or phrase creates is its connotative meaning. This is an important distinction because when we write or speak, we either deliberately or often unknowingly choose a synonym which reflects how we feel about the person or subject we are writing or speaking about.

Here's an example from Prof Vosovic of Stanford University. Consider the word 'cat'. The denotative meaning (how the dictionary defines 'cat') is: “a carnivorous mammal, domesticated as a rat catcher or pet.” But what is its connotative meaning? It depends. If you like cats, the word “cat” may suggest graceful motion, affectionate playfulness, noble reserve and admirable self sufficiency. If you don’t, the word might suggest stealthiness, spitefulness, coldness and haughty disdain.

When many words with strong connotations appear in the same news report, that news report is said to be 'slanted' or 'loaded'. This means that the words have been chosen to create either a favorable or unfavorable impression. Professor Vosovic of Stanford University has written the following two different accounts of the same event. Briefly discuss the differences in the use of words.Which words in particular create the effect?

A. Five teenagers were loitering on the corner. As their raucous laughter cut through the air, we noticed their sloppy black leather jackets and their greasy dyed hair. They slouched against a building with cigarettes dangling contemptuously from their mouths.

B. Five youngsters stood on the corner. As the joy of their laughter filled the air, we noticed their smooth loose-fitting jackets and the gleam of their colorful hair. They relaxed against a building smoking evenly on cigarettes that seemed almost natural in their serious young mouths.

Consider the following example from recent Australian immigration debate. Depending on which side of the argument you are on, asylum seekers are

variously referred to as boat people, illegal immigrants, unlawful aliens, queue jumpers etc. Depending on which of these terms you use, your attitude to the immigration debate can be gauged as positive or negative. For example, the term asylum seeker has a positive connotation suggesting distress and the need for compassion. Illegal immigrants has a negative connotation that implies unruly incursions by possibly dangerous people.

In this context, Monash University's Prof. Robert Manne wrote in this article in 2002 of the language used by Howard government Minister for Immigration, Philip Ruddock. He said in part:

For him, a broken child has suffered 'an adverse impact'.; people who go on hunger strikes or sew their lips together are involved in 'inappropriate behaviours'; refugees who flee to the West in terror are 'queue jumpers'; those who live without hope in forlorn refugee camps are 'safe and secure'; those who are despatched to tropical prisons financed by Australia are part of the 'Pacific Solution'.

By teaching Australians to think and speak like this, the minister has gradually helped to reconcile a goodly part of the nation to the unspeakable cruelties enacted daily of the kind we were able to witness on Lateline last week (Manne, 2002, 11).

Practical Exercise 2: Complete both parts of this exercise. Can you think of other English words which will have different meanings in different contexts?

A In each sentence below substitute another word or phrase for the word 'means'.

a He means more to me than a meal ticket.

b I mean to qualify for the Olympics in 2000.

c What do you mean, ‘unqualified at present’?

d What actually is the meaning of this painting?

e H2SO4 means sulphuric acid.

f My Lotto prize means I can tell the boss what to do with his job tomorrow.

g I mean, why can’t you go to the movie with me tonight?

h Here comes Shari looking angry, and I mean ANGRY.

B. Choose another word which means the same (not the opposite) but which has a different connotation (ie implied meaning, either positive or negative). The first one is done for you.

a. You are skinny ……… I am slim

b. You are ……… I am daring

c. You are fussy ……… I am …………

d. You are careless… I am ………

e. You are lazy …… I am ………

f. You are …… I am chatty..........

Research Exercise 3: Carbon tax and other 'dirty' language

Just as the immigration debate in Australia uses highly charged language, so does the debate over the Carbon tax and Australia's response to global warming. Read this recent article from the news site On Line Opinion. Consider the different connotations of the phrases 'climate change' versus 'global warming', 'carbon tax' versus 'carbon pollution reduction scheme', 'tax' versus 'levy', 'sound science' versus 'junk science'. How does using the language of economics change the way the debate is framed and the willingness of Australians to take action?

So what has this to do with professional writing?

Writing obviously uses language and the point of getting a handle on the complex subject of language is that as writers we need to be conscious of the fact that our notions of meaning expressed in the words we choose, may not necessarily translate into the same meaning in the minds of our readers or audience. While we will look at the audience in more detail next week, here are a couple of important points to remember about the relationship between the writer and the reader. Daniel Chandler (1995) in The Act of Writing argues that:

hard to understand.

hard to understand.